Cloud adoption has flourished under COVID-19, thanks to the twin tailwinds of work-from-home and digital transformation. But escalating cost is emerging as a top problem as customers seek financial relief from public cloud platforms, which have become the biggest corporations in the world.

When going into discussions with your friendly neighborhood cloud provider to set terms for the next contract, don’t feel bad if you get the sense that you’re completely outgunned and overmatched by a superior foe. The cloud vendors are well aware of who has the upper hand, and it’s not you.

“The paradigm has really shifted,” says Aran Khanna, a former AWS engineer who is now the CEO and co-founder of Archera, a provider of cloud optimization solutions. “Instead of going to Dell and going to HP and making those reps give you the best price with best financing terms, [the cloud platforms] are basically saying, ‘Hey here’s all the data on how you could purchase things. Here’s all pricing. We don’t deviate from this.’ And it’s a 2 gigabyte file!”

Clearly, no human is going to be able to comprehend all the different parameters that go into setting prices for compute, networking, and storage resources in the cloud, Khanna says. What size instances should you buy, and for how long? Should you go serverless? What about using the cloud vendor’s managed services?

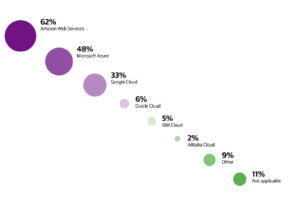

AWS remains the most popular public cloud providers, per O’Reilly’s survey (Source: O’Reilly’s “The Cloud in 2021: Adoption Continues”

Want to compare one cloud’s offer with the offer from another cloud? Good luck with that. There are no standard SKUs, and you’ll need to do a lot of the translation yourself, Khanna says.

“There’s no apples to apples in the contracts, and they provide different flexibility over different dimensions,” he says. “One provides flexibility over compute instances and serverless. One provides flexibility over storage and serverless. So you can’t really compare the different commitment times, even between these vendors, which makes it very difficult for someone to reason about this in a spreadsheet. There are like 50, 60, 70 different dimensions, frankly, that you have to then go and work over. And maybe 50% of them are irrelevant to your use case, but you don’t know that if you’re just a finance person or just the engineer.”

So what’s the result of all this engineered complexity by the largest, most technologically sophisticated companies in the world? For most companies, they overprovision, because the downside of buying too little compute, storage, and networking would be detrimental to their operations. That’s a pernicious little twist on the paradigm shift that may have caught you by surprise.

The cost of cloud computing was the number one concern cited by respondents to a recent survey conducted earlier this year by O’Reilly Media. Of the 2,834 subscribers who took the survey, 30% cited cost as the most important concern, followed by modernizing applications using public cloud containers at 19%, and optimizing cloud performance at 13%.

“The common perception that cloud computing is inexpensive isn’t reality,” writes Mike Loukides, O’Reilly’s vice president of content strategy in the new report, titled “The Cloud in 2021: Adoption Continues” (the report can be accessed here).

“Being able to allocate a few servers or high-powered compute engines with a credit card is certainly an inexpensive way to start a project, but those savings evaporate at enterprise scale,” Loukides continues. “The cloud provider will reap the economies of scale. For a user, the cloud’s real advantages aren’t in cost savings but in flexibility, reliability, and scaling.”

IT decisionmakers who try to replicate the old way of provisioning compute resources as their operations move to the cloud are likely going to end up on the wrong side of the equation when the costs and benefits are tallied up at the end of the quarter, says Khanna, who helped implement Sagemaker at AWS and also worked on provisioning GPUs on the cloud while working with Nvidia.

“The processes that were in place for many, many years, where procurement is running ahead of the purchasing, has been sort of flipped, and now they’re running behind. Finance comes in after the fact, instead of before the fact,” Khanna tells Datanami. “So a lot of old school organizations just don’t know how to reason about this new process. And what ends up happening is you get spreadsheets going back and forth for three months and meetings and all of this sort of cruft that really isn’t necessary, but that is how the best practices of the world have evolved today. And that’s the problem we’re trying to solve.”

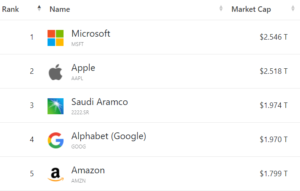

Three of the five largest companies by market capitalization are public cloud providers (Image Source: Google)

Archera develops software that helps customers automate many of the manual processes involved in ramping up cloud resources. It’s goal is to drive predictability for clients, and usually costs come down as a product of that, Khanna says. In the event that a client overprovisions, Archera will promise to buy the unused capacity back, which it resells to another client, providing a form of insurance.

The Netflixes and the Airbnbs of the world have figured out the new cloud computing game, and are able to play the cloud vendors against each other and negotiate contracts that serve their best interests. But smaller companies without that engineering heft typically lack the resources that are required to truly get a handle on the way compute resources are priced and sold in the cloud, which leads to poor financial outcomes.

While the cloud vendors do offer some tools, it’s best not to rely on them, Khanna says. The tools that he helped develop at AWS were reactive, instead of forward thinking, and led to lot of sub-optimal outcomes and wasting of engineering resources.

“There are levers and knobs that you can go and learn about…but it’s too little, too late and it’s very complicated,” he says. “You have to go learn it and last-mile it for yourself. It’s engineering time at the end of the day, so that’s sort of the trade-off. Do you want your engineers basically stringing together Amazon tools? Or do you want them driving top line and running more models?”

But don’t lay the blame for this situation on AWS, Microsoft Azure, or Google Cloud, which collectively have a market capitalization of $6.3 trillion. It’s clearly not in the interests of those companies to figure out how to reduce what you spend with them. They are for-profit entities, at the end of the day. It’s not their fault that you can’t restrain your engineers from spinning up 1,000-node clusters with just a few clicks of a mouse and a 16-digit credit card. Besides, the problem spans multiple clouds.

“Amazon is not going to solve the problem across the stack when stack sits in Snowflake, it sits in Kubernetes, it sits in a BigQuery table, and it sits in their hardware,” he says. “They’ll solve their hardware piece of it, maybe, if you’re a big customer and they’ll do that once a quarter instead of in real time. But at least they’ll help you there. But they won’t help you with the rest of it.”

One of the signs of the cloud dilemma is a surge in popularity of observability solutions, which use big data techniques and AI to keep track of the server, storage, and application sprawl now enveloping even mid-size companies.

Getting a handle on escalating cloud costs was the driver behind Anodot’s recent acquisition of Pileus, a developer of FinOps solutions. Customers want better ways to manage those costs, said Anodot, which cited a 451 Research report from 2019 that found 69% of firms regularly overspend on their cloud budget by at least 25%.

“We have witnessed first-hand the many challenges organizations face while attempting to manage their cloud costs,” Anodot CEO David Drai said in a press release. “Historically, cloud pricing and billing has been a complicated undertaking for many organizations–until now. Today, Anodot joins forces with Pileus to combat this growing problem.”

The combination of Anodot’s machine learning and Pileus cloud spending management software will result in the development of “an advanced forecast and anomaly detection” system that’s not only based on the cloud cost history, but factors other business metrics into the equation.

The march to the cloud is not going to slow down. In fact, according to Gartner, public cloud spending will exceed 45% of all enterprise IT spending by 2026, up from less than 17% in 2021. Ultimately, companies that get a handle on the way public cloud vendors package and sell their offerings will have a competitive advantage over those that don’t, which should give plenty of motivation for the finance team to bring spending on compute resources back under control.

Related Items:

Rush to Cloud Exposes Budgetary Pitfalls

Big Data Apps Wasting Billions in the Cloud

Cloud Analytics Proving Costly for Some

The post Cloud Getting Expensive? That’s By Design, But Don’t Blame the Clouds appeared first on Datanami.

0 Commentaires